Chapter 7. The Old Library

"Then I said unto them, what is the high place where unto ye go?" | ||

| --Ezekiel xx | ||

To the man who would take up night climbing seriously, the Old Library offers an ideal nursery. No dons or porters will disturb his first clumsy attempts, no proctor who hears him is likely to guess the Source of the noise. He may pad about fearlessly in his dark gym-shoes, and concentrate only . on the climbing problems before him. The absolute novice may let in the first gear on easy climbs, and the advanced expert will still find work worthy of his efforts. The only nocturnal inhabitant, the caretaker, lives in the south-west corner, overlooking King's, and far removed from the climbing side. So if the novice will come along with us, we will try to arouse his enthusiasm and whet his appetite for further expeditions.

As we pass down Senate House Passage from King's Parade to Trinity Hall, the Senate House on our left gives way to some iron railings,connecting it to the highest part of the Old Library. It is these railings that we must cross.

Broad and pointed like a row of prehistoric javelins, they are nevertheless very blunt, and the novice may tackle them without fear of injury. If he should find them difficult, a press-up will help him. When the hands are level with the hips, he can raise a foot on to the narrow horizontal ribbon running nine inches from the top. Having got across, he may lower himself as best he will. The easiest place to cross is the side of the gate half-way along the railings, although it is under the full glare of a lamp-post. A projection sideways here makes the balance easy, whereas crossing the straight line of railings farther along is rather difficult. As he turns on the top of the railings, the Gate of Honour in Gonville and Caius shows itself within five yards of him, across the passage.

We are now on the scene of action. On the right is a large double doorway above which is written the word Biblioteca. A huge awning-ledge projects for about four feet above it, at a height of ten feet from the ground. Here Eager Egbert can try his first climb. This is to get on to the top of the awning ledge.

As a sheer feat of strength this is difficult, but it can be made easy by chimneying at the side as a help to the pull-up. With his head level with the ledge, the climber may remove both his hands to show that the body can be supported by chimneying alone. Some iron bars on the window above give additional help, but the climber can go no farther than this ledge. If a novice can do this (and it is not difficult) he can become a good climber.

Immediately in front of us there is a drain-pipe, running from the ground to the roof, a height of between twenty-five and thirty feet. This is the Sunken Drain-pipe. Five yards to the right is a gap between two walls, running up past two windows. This is the Old Library Chimney. We will leave both of these for the moment and proceed to the far railings, by King's.

Passing along an archway with pillars on the left, we come to the high railings separating the Old Library from King's. Along the top is a row of revolving spikes, so that the railings cannot be climbed direct. This does not matter, for it is the building on which we want to climb, and not the spikes.

As seen in the photograph, the stone is slotted, but the slots are V-shaped, and sloping, so that they cannot be used as a ladder. Nevertheless, it is possible without much difficulty to get on to the ledge above the railings. It might be possible, but would be extremely unwise, to go higher, and in our opinion the roof could not be reached by this route. Even if a climber could get near the top (as he might, on a rope), he would be confronted with an insurmountable overhang. So let him go to the right, where a saintless niche confronts him. Here he may ensconce himself, and imagine for a few minutes that he is petrified, with a stony halo round his head.

A Kingsman will observe that this offers an illicit method of entry into his college. Furthermore, it is a genteel way which he can use without soiling his knees and elbows, should he be in evening dress. We give it without compunction, because there are half a dozen easier ways.

Ten yards along to the right there is another niche, also saintless, which can be reached from the ground. This is a difficult bit of climbing, requiring a delicate balance. Starting immediately under the niche, one must make use of the archway on the right, with an under-hand grip. This helps to prevent one from falling outwards. The niche sinks deep into the wall, so that having reached it one may rest in comfort.

An exactly similar niche, except that every hand-grip is reversed, is to be found at the other end of the pillars. By climbing up to each of these niches in succession a climber may, if he wish, compare the efficiency of his right side with that of his left. The difference may astonish him.

We will now go up to the roof.

There are two routes up, both of which will be severe to a novice. These are the Sunken Drain-pipe and the Old Library Chimney. We will take the latter first. It is to be found twenty yards from the Senate House Passage railings, on the right. The climber must face south, as the windows on the . south side come too close to the side wall to leave room for the climber's body. On the north side a buttress leaves a recess into which a man's body fits nicely. The chimney is too broad for comfort, and a very short man might find it impossible to reach the opposite wall, with his feet flapping disconsolately in space like an elephant's uvula.

The second window comes very close indeed to the wall, and the feet must keep to a vertical strip of stone only three inches wide. Proceeding indomitably upwards, we bump our head a nasty crack and pause to think.

The recess between the buttress and the wall suddenly ceases to exist. From being too broad, the chimney becomes too narrow. Some convenient brick-ends projecting from the wall above make further progress possible. To be able to make use of them we must have our back against the opposite wall. Turning round in a chimney is not easy, but holding on to a brick-end with one hand we can make a gymnastic twist, and from then onwards the climb is easy. [1] With the brick-ends before us, we can do the last six or seven feet up to the roof behind us in comfort.

Now down again, to the Sunken Drain-pipe. This offers a climb which even in Cambridge is unique. Being sunk, as the photograph shows, between a projecting wall and a buttress, it prevents the climber from getting both feet on it at once. He must use the slotted stone-work on the left. The pipe is slightly farther away from the buttress than from the left wall, and leaves just enough room to wedge the right foot. The right hand can just get a grip behind the pipe.

The left foot is stretched right out to the side, to the edge of the projecting blocks of stone. Getting it as high as possible, press hard on it, at the same time shoving hard with the right foot, pulling outwards with the right arm, and to the right with the left hand against the edge eighteen inches away. It looks fiendishly severe but is actually quite easy.

For the last ten or twelve feet the recess widens, and it is possible to get both feet beside the pipe. The stone is rough, and for this short distance you can walk straight up. There is a loose corner-stone at the top of which the panting novice must beware; it is quite easy to tell which it is and to avoid it. The climber who has reached the roof by these two methods need consider himself a novice no longer.

Figure 7-4. Sunken Drain-pipe. Upper half.

It was on this part of the pipe that disaster nearly occurred to one of our party.

A few lines above a sentence starts, "There is a loose cornerstone". For "is" read "was", and we will explain why the tense has been changed. After we first wrote this chapter, five climbers went up to obtain a photograph of the Tottering Tower. Two were I already on the roof, two were on the pipe ten feet apart (the upper man almost on the roof) and the writer nearing the top of the chimney on the right. The upper man on the pipe, to rest for a few moments before the final pull up, placed his left elbow on the corner of the ledge on the left. We had forgotten to warn him, and he said it looked quite safe. Although he exerted little pressure, a whole length of the ledge, eighteen inches long, and weighing some thirty or forty pounds, broke off and fell.

Now comes the extraordinary part of the tale. The climber below was holding on to the pipe with both hands at the same level, waiting for the man above to leave his way clear. The stone, falling across his arms, cut a gash through his tweed coat and shirt, and made a nasty cut in his arm, besides grazing his head en route. But his two elbows acted as a spring, taking the greater part of the shock, and after laying the stone on the ledge on his left, the climber was able to complete the climb. Had we taken our own advice in a previous chapter never to have two climbers on a pitch at the same time, this flirtation with calamity could never have happened.

The lower climber afterwards told us that he was not frightened by the stone falling. What he found unpleasant was looking up a few moments before, when he saw a chink of light between the ledge and the wall, and knew that the stone was about to fall. His suspense was prolonged for a second or two by the upper climber holding on to the stone until his strength gave out.

The upper climber was slightly shaken by this incident. He did not allow it to affect his climbing, but several times in the next night or two he looked thoughtful. On the way down he had already lowered himself over the edge when his hold on the roof stiffened. He came up again and said the top of the pipe had broken.

At the time this seemed almost as serious as the previous incident. Had he released his hold on the roof, it seemed he must have fallen. The writer, who had witnessed the first episode, began to wonder whether the luck had turned, and experienced some nasty sensations. They came down the chimney and the others, who had gone down the pipe, said the bowl was loose but the pipe safe. The man with the gashed sleeve was entirely unmoved, and would hardly be persuaded to keep the stone as a memento. And now back to the Sunken Drain-pipe.

About fifteen feet up there are two ledges, three feet apart. The upper one is three or four inches broad, and inclined to be crumbly. The lower one is only an inch or two broad, but perfectly safe. These two ledges are known as the Old Library Traverse. We have never been the whole way along (which extends as far as King's) but it is a recognized climb. 38 When moving the hands along the upper ledge, slide them along and never take either hand completely away.

There is a third route, as far as we know not yet exploited, whereby the roof could be reached from the ground. This is between Trinity Hall and the north gate of King's, on the left as one faces south.

In a recess between a rounded wall and a bay window, two pipes run upwards to the roof. After prolonged study from the ground we decided it was a possible climb and magnanimously left it for future generations to conquer. It is a height of forty to fifty feet, and we cannot say whether it would prove easy or very severe.

Seen from the top, it looks severe. Further, the last stretch of pipe rattles, although it seems safe enough. A couple of climbers, prowling round the roof, decided to have nothing to do with it.

Once the roof is reached, the Old Library offers one further climb. All the different roof-levels are connected with iron ladders, and it is possible to wander at will in all directions. a There is no particular need for silence, but remember the caretaker in the south-west corner.

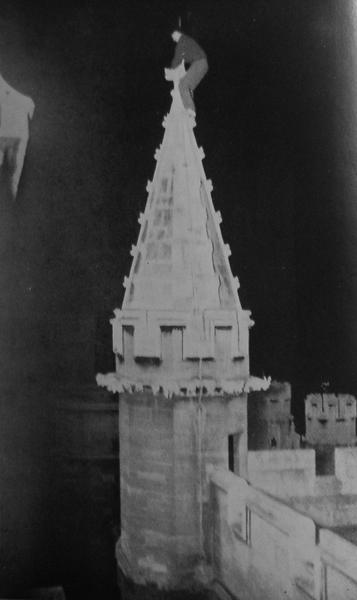

The climb which remains to be done is that needle-shaped erection on the west side, which we have named the O'Hara Pinnacle or Tottering Tower. The climber in the photograph will now take the pen.

Figure 7-6. The O'Hara Pinnacle or Tottering Tower.

The O'Hara Pinnacle or Tottering Tower. At the moment of taking the photograph the top cross, which the climber is holding, was swaying. Note King's Chapel in the background.

"Once on the roof the climber turns right until he reaches an iron ladder, perhaps fifteen or twenty feet high. This he ascends and, turning left, walks along the foot of the roof. This is easy, as there is the usual parapet and broadwalk. At the end of this roof we descend into a small area or sunken well. Climbing out of this (it is only about eight feet deep) we emerge on a broad, flat roof with a pinnacle at its near left-hand corner. The pinnacle is perhaps twenty-five feet high and presents little difficulty. Standing on the parapet of the roof, one holds on to a gargoyle with the left hand and to a ridge above it with the right hand. Now pull up and place the left foot on another gargoyle. This is the most difficult part of an easy climb and should prove easy even to the most inexperienced, as there is only a short drop (about six feet) to the roof below. The rest is easy. The pinnacle is studded with small carvings which are perfectly sound, and one walks up them as one would up a ladder. At the top there is a good view of the lighted town, and little or no chance of the climber being seen by inquisitive eyes."

The name "Tottering Tower" was given because two of the party swore that the top of the pinnacle swayed just before the photograph was taken. This climb, though fairly easy, looked extremely dangerous, because the climber had to trust small knobs about the size of a fist.

Those who look upwards by day will have noticed the two stone arches on the top of the north side. These, when one is close up to them, are surprisingly big. We said there was only one climb on the roof; these form a possible exception to our statement. They are ten or twelve feet high, and could be climbed either by the human ladder method, or by a wire-ribbon lightning conductor. At present however the conductor is flush with the wall, very neat and tidy, so we suggest the human ladder. Also, it is seldom wise to trust a lightning conductor near the top.

And so we will pause, to look at the view.

From here on a moonlight night one has a fine view of Cambridge. To the south King's Chapel looms mysteriously, its tapering spires stretching upwards towards the scudding' clouds in unrivalled grandeur. We are level with the tops of its windows, sixty or seventy feet up, yet it still seems so gigantic that we might be looking at it from the ground. We cannot help envying those two climbers down on the roofs of Trinity Hall who once heard a neighbouring party climbing on the chapel. What emotions would it not arouse if from here we saw two climbers near the top of those needle-like spires, small and ant-like, silhouetted minutely against the hugeness of the sky?

And then, to the north, St. John's Chapel stands out menacingly across a sea of roof-tops, to send us back from excitement to a shuddering foreboding. Rumour says that it has only once been climbed, and then by a party of experts, heavily roped. Even the participants are silent on this subject, and rumour continues its tale that one of them fell off, and owed his life to the rope. Lest others should attempt the ascent of this terrible climb and perish, they swore themselves to secrecy (telling only enough people to ensure the perpetuation of their epic) and went off to try Everest instead. In vain we have tried to find out more about this climb; the echoes of the past are muffled.

The photographers have not yet attempted this building; that is why we shudder as we stand on the Old Library and look at it.

Below us the roofs of Trinity Hall strike a more cheerful note. There is nothing at all exciting about them, but it is pleasant to look down on them from such a height.

A sound of steps in Senate House Passage brings us to the. edge, full of peeping curiosity. A proctor is passing below, moving until his head is in a direct line with his feet, a speck without height. Rather inconsequently, we wonder what would happen if we spat, and how far his august form would have moved from the point of impact. Would he attribute it to an owl or a bat? Or would he continue imperturbably on. wards, like Queen Victoria with a couple of train-bearers? We shall never know.

The roofs of the Old Library are an infant's paradise. Everything is uneven, a jumbled confusion of slopes, leaded walks, iron ladders, and rotten planks bridging shallow gaps. The whole forms a square, built round the inner court where law students now swarm by day. It is great fun exploring all round, and one always hopes to find a store of bags labelled "gold", and stowed away by some medieval villain. And if one fails in this one may at least find, as we did once, a builder's collar and studs, forgotten in the rush to down tools. The more naughty members of the party may feel the urge to cry "boo" to the caretaker to see what action he will take, but they should be restrained. Crying "boo" at people is not consistent with good climbing.

And now it is time to go home. Eager Egbert is in lodgings, and must be in by twelve. That is why he will not always be able to come with us unless — well, it's a top-floor window, but after this he might be able to get up to it. Knowing Egbert, we think he will.

And so good-night. And remember, Egbert, please, black gym-shoes and not those white things you use for squash.