The Roof-Climber's Guide to Trinity

Dedication to the author of the first edition

There is something a little tragic about a second edition. It means the passing away of the freshness of the first explorations, and the coming of refinements and artificialities. For all that, the present generation of climbers, though they may hang by their proverbial eyebrows from imperceptible holds on rotes only recently discovered, do not forget the debt they we to the pioneers, and especially to him who lit the torch which has inspired so many successors through three decades.

Introduction to the first edition

"Ille te mecum locus et beatae postulant arces." --- Horace.

In these athletic days of rapid reversion to the Simian practices of our ancestors, climbing of all kinds is naturally assuming an ever more prominent position. Since the supply of unconquered Alps is limited and the dangers of Nature's monumental exercise grounds are yearly increased by the polish of frequent feet and the broken bottles of thirsty souls, aspirants with the true faith at heart have been forced of late years to seek new sensations on the artificial erections of man. Such is the origin of modern Wall and Roof Climbing. The discovery that these empiric sciences were in reality of enormous antiquity, possessing an extensive history and a literature which includes the greatest verse and prose writers of all ages, has done much latterly to assist their enthusiastic redevelopment. This branch of the subject is dealt with in the pamphlet "Wall and Roof Climbing," [1] which contains a short outline of the history and literature, ancient and modern, and an account of the laws, methods, appliances, and phraseology peculiar to the art. The interest shown by many Cambridge residents in the opening up of these new fields, and the vigour with which, in one college at least, the exploration has been prosecuted, gave rise to the idea that a brief Guide to the points best worth attempting, with a few suggestions as to the routes most favoured by the early climbers, might be found a convenience. The present leaflet is the result; the precursor we hope, if successful, of similar introductions in other Colleges to regions too long neglected by resident and visitor alike. Doubtless the fact that a certain bashful conservatism has confined the excursions hitherto to hours of the night has done much to induce this orophismic philistinism. But Alpine ascents suffer under a similar disadvantage, and we confess that, however illogically, we should view with regret any alteration in the College regulations tending to soften the conditions. The darkness, besides comfortably concealing the accumulating soot on hands and person, surrounds the venture with an air of vague mystery, and lends a pleasing uncertainty to the handholds, a depth of impressive gloom to the courts and gutters and a shadowy outline, fraught with terrors, to the colossal-seeming towers, that could hardly be spared; while the recurring step of the night-porter, heard when the climber hangs in literal suspense in some awkward lamp-glare, rouses thrills of the chase unknown to legalised stegophilism. Unconventional routes in and out of College are purposely left unmentioned; they are an all too popular abuse of a noble science. Much is here passed briefly over, which in a more exhaustive account would call for longer notice; much also in the College still remains unexplored. The next few years will doubtless see a great advance both in the count of "possible" climbs and in the methods adopted in negotiating old ones. For ourselves non-residence has closed our period of exploration; but we hand on the work to other feet with a full confidence in the powers and numbers of the ever-increasing fraternity who cherish as their motto Browning's lines --- "Though there's doorway behind thee and window before, Go straight at the wall."

Introduction to the second edition

"Hitch your wagon to a star and you'll soon get to the top of the tree." --- American Film Caption.

Thirty years have passed since the first edition of this book appeared. Even in Trinity the hand of the mason has not been idle, and during these years many new landmarks have appeared in the range. Exploration, too, has been going steadily forward. The conquest of the Great Gate in November, 1927, marked a new epoch; and so many fresh climbs have been discovered in the subsequent three years, that a fuller edition of the old guide was felt to be desirable. The original guide divided its climbs into Routes. With so much new matter this would involve too much hesitation by the wayside, and so this new volume describes the range court by court with an occasional separate chapter for prominent peaks. The chapters on New Court and I Court have been very little altered for this edition. The rest has been entirely rewritten: but the author of the original edition has fortunately been able to read and comment freely upon the manuscript, and his suggestions have been gratefully incorporated into this. The old quotations, too, have been used again and a few new ones added. If we may be permitted a word of warning --- the Trinity Roofs have an unblemished record. In thirty years there has been no known injury to the framework of a building or of an undergraduate. The 'polished corners' of either will only remain immune so long as the good rules and traditions hitherto governing the sport continue to be observed --- the rules of sober and competent leading, of tactful handling of the material and the officials, of sound grounding in climbing technique, and of slow beginnings on the part of "the schoolboy, fresh from school." The cardinal climbing offences have been pilloried once and for all in Kipling's lines :- "By the rubbish in our wake, by the noble noise we make, Be sure, be sure we're going to do some splendid thing."

New Court

"Lead, lift at last your soul that walks the air Up to the house front, or its back perhaps --- Whether façade or no, one coquetry Of coloured brick and carved stone. Stucco? Well The daintiness is cheery." --- Browning

"Heroes tall Dislodging pinnacle and parapet." --- Tennyson

Complete Circuit

Time, 45 to 60 minutes; guide superfluous, but rope necessary; expense repair of pipes and possible doctor's fees.

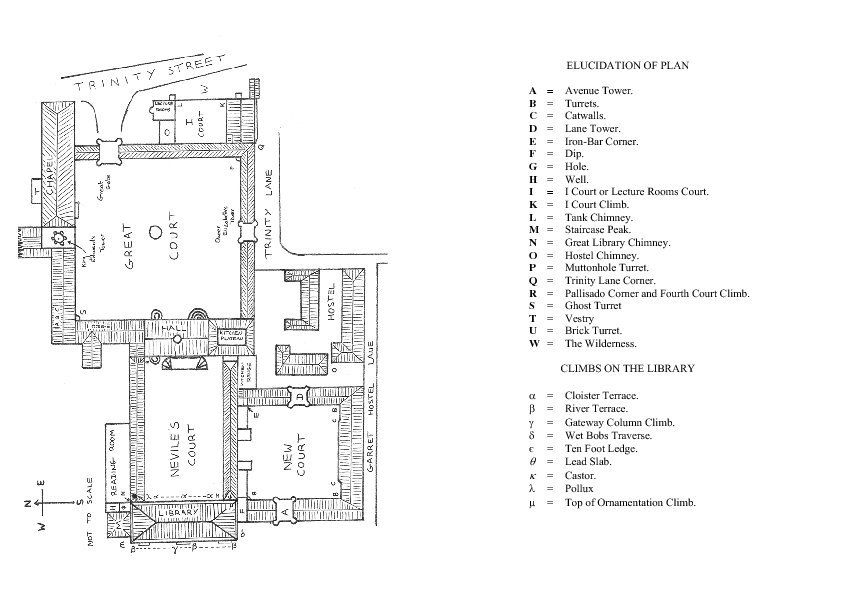

The Avenue Tower

The start of our route is made from some window between the Avenue Tower (A on plan) and the Dip (F). The leads can be followed either on the Court of the Cam side until the wall of the Tower is reached. Here the slant roof is ascended over the dormer until near the summit of the gable, when the hand is able to reach with a stretch the edge of an embrasure above; the help of a small ledge some four feet up, being hardly required for the swing up on to the roof. The Turrets here may divert our efforts for a moment; but in deference to the slumberer below, whether don or undergraduate, it is best to pass rapidly round a convenient ledge on the inside of the battlements, which removes the necessity of clambering over the roof. The descent is made by the corresponding embrasure on the opposite side, the arms at full length just bringing a tall man's feet to the roof.

The Corner Turret

The leads continue on either side. But if the Cam side route be taken, the lack of battlements and path above Garret Hostel Lane, compels a return across the gable at the corner, after a glance over the sensational precipice above the lane, and the climber finds himself at the foot of the Corner Turret, his first "roofside problem." If he be tempted to solve it on his way, the only necessary formula (as also for its duplicates B.B.) is a friendly back up and the use of a somewhat loose pipe. Care should be taken to avoid touching the summit battlements, as they collapse at a breath.

The little "Catwalls" (C;C) next present themselves but no difficulty—except to weak heads; and at the next Corner Turret (B) it is possible either to cross again to the Trinity Lane and less comfortable leads, of to follow the ordinary track to the foot of the Lane Tower (D).

The Lane Tower

This is a more difficult subject than A and has proved a stumbling block to many. Ascending over the dormer, of close to the wall, it is possible from near the top of the gable for a long reach to get some fingers of the right hand over an embrasureedge; if the left foot be then raised sufficiently high, a just attainable ledge serves as a foothold,—and the rest is mechanical. It is not wise to trust exclusively to the hand, as the cement has more than once proved to be brittle and to have precipitated a whole party into the gutter. A friend's shoulder will always solve the difficulty for a short reach. It is safest not to linger here for the view, and the descent is similar to that from the Avenue Tower.

Iron-Bar Corner (E)

(The iron bar itself has now disappeared, but the old name may with advantage be kept). The next check occurs at the corner, whee the joining of Nevile's Court and New Court is flawed, a narrow piece of tile roof, simplified by the flat lead tops of two windows, alone connecting them. It is an exposed step down about three feet, from the parapet at the top of the New Court gable, on to the first window top.

Two alternative routes are now possible. One leads to the right, beyond a tile gable, down on to a broad ledge, round an awkward chimney stack, and so on to the bicycle track [2], close to the corner above the Junior Combination Room. But this cannot be accepted as a genuine New Court Circuit. The correct route runs along the New Court side of the Cloister roof, over a succession of cross gables, past the turrets (B.B.) to the Library corner.

The Dip

The last and worst difficulty of the circuit has now to be tackled, one which much troubled the early climbers. It is formed by the low block of buildings connecting the corners of Nevile's Court and New Court, and its deep-lying roof is thus overtopped by the higher walls of either. It goes by the name of the Dip (F on plan). The Dip is separated from the Hole (G) by a high battlemented wall which joins the Nevile's Court roof to the Library and forms the narrow "takeoff" for the descent. A door at the bottom of this wall, if not as usual locked, must of course be ignored. The first step is apparent, a sloping ledge some four feet below the battlements; but no further steps are forthcoming and the climber has to perform the delicate task of transferring his hands to his foothold and thence being lowered or dropping. The crumbling mouldings of an intervening window complicate rather than assist, and if the help of a rope doubled round one of the battlements be not used, the first part will always prove an exciting balance-test for the last to descend. The ascent of the New Court wall is made in the corner formed between the wall and either turret. The tallest of the party is placed firmly in the corner and the leader scrambles to his shoulders, using the rainpipe as assistance. By the aid of a handhold on a ledge encircling the turret, he can now secure a position on the basin-like top of the pipe, and thence reach the firm parapet ledge and pull up. This pitch has recently been climbed without the aid of rope or shoulder, using the rainpipe and thrusting an arm into the hole behind its basin. The pipes are fragile and should be dealt with gently for the sake of future generations.

If the Circuit of the Court is taken in the opposite direction, the two difficult Dip pitches are naturally reversed. The descent from the New Court roof into the Dip will not cause much delay, but the climb up the wall on the opposite side is correspondingly more difficult. The more exposed method is for the leader to take off from the top of the retaining parapet on the Court side; a severe pull-up on the sloping ledge will enable a tall man to reach the battlements. Or the leader may take off from the shoulders of a friend sitting astride the parapet. A safer way, also very difficult, is to gain a stance on the hood-moulding above the "intervening window"; this is reached by jockeying a foot up the central window pillar, using a finger hold behind one of the floral ornaments on the sloping ledge above; from this cramped position a stretch is made and the battlements grasped. Most leaders find reassurance if their feet are held on to the sloping hood-mounting by the second man, while the last stretch is being made.

Nevile's Court

"Auream quisquis mediocritam Diliget, tutus caret obsoleti Sordibus tecti, caret invedenda Sobrius Aula." --- Horace

"But let my due feet never fail To walk the studious Cloister's pale, And love the high-embow'ed roof With antique pillars massy proof." --- Milton

"Here we go in a flung festoon Half way up to the jealous moon." --- Kipling

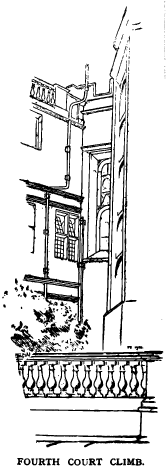

In Nevile's Court, three climbs, by which the roofs can be reached, start from the ground. This is always a desideratum in College climbing, since it frees us from the window-whims if attic occupants, and is all too rare on the work of lesser architects than Wren and Nevile. Two of these climbs, Castor and Pollux, are described in the chapter on the Library (page 36). The third lies in the ample recess in the northeastern corner of the court, between the wall and the great bastion of Hall. For geographical reasons this is called the Fourth Court Climb.

The Fourth Court Climb

A lilac bush behind the balustrade may serve for screen, until the light through the frosted glass assures us that we have the climb to ourselves. An easy movement, a lie-back with the right hand and a press-up with the left, and then an almost similar one with help from the open window, establishes us above the light. From here a broad ledge can just be reached with the hand, and a pull up on a small subsidiary ledge assists us on to it; the drain pipe again affording a grateful lie-back hold. This ledge provides the first breathing space.

A step then brings us on to the sill of the first flor staircase window. Lie-back holds for either hand, left in the window and right on the pipe, pull us on to the stone bar of the window; from which the next broad ledge can be reached. A pull up on to this, with considerable help in steadying from a round drain pipe above; and then another breather before the last and most fearful pitch.

One moment of doubt is dispelled by the white upturned faces of the rest of the party, still crouching under the lilac bush far below. A step on the the angle of the serpentine pipe only allows the average man to touch the leaded ledge above. So near and yet so far. Digging the fingers deep into the drain pipe we scramble to reach, first the ledge and then a higher wriggle of the serpentine pipe; and quickly disappearing over the balustrade we are on the "bicycle track."

To grasp the ledge above the final pitch requires a reach of 8 feet 3 inches from tiptoe. As the majority of people cannot manage this, the climb must be classed as severe because of its extreme exposure. The leader should not rope for this climb, as the weight of so great a length might drag him backwards off the final pitch. If help is needed, a rope should be lowered by a friend from above.

Let us return and undertake the main "roof level expedition," the circuit of the court, a climb frequently combined with the circuit of New Court. We will therefore assume that the party has taken the first alternative offered, in the New Court chapter, after leaving Ironbar Corner, and is now standing in the south-eastern angle of the court roofs, above the Junior Combination Room.

The Circuit of Nevile's Court

This takes from 20 to 30 minutes and is a simple affair, though admirable training for a beginner. We will start in the direction of Hall. For 30 feet after the corner, the leads are narrow and the parapet low, but after we gain the shadow of Hall by the three steps so thoughtfully provided for the purpose, these terrors disturb us no more. At the far end of Hall an awkward and exposed step, over the battlements and down on to the balustrade, brings us on to the bicycle track at Palisade Corner, at the top of the Fourth Court climb.

The bicycle track leads with Roman directness to the Library, whose inner or eastern face we must now traverse. This is done by the Cloister Terrace, which is fully described in the chapter on the Library (page 38).

When the opposite side of the court is reached, a further stretch of the bicycle track brings us back to within 20 feet of the south-eastern corner. Here a low wall and drain pipe must be stepped over, and in the corner whence we started, the coping will be found surprisingly warm to the touch. A moment's thought will provide the solution. It is a flue.

In the course of our circuit we have firmly resisted all temptations to stray aside. Two diversions may well be made.

The Hall

The ascent of Hall is best made at the Lodge end on the Nevile's Court side. Let the author of the first edition describe the scene.

"The slightly raised coping which edges either end provides the key. Holding its square edges with both hands and placing his feet on the narrow lead gutter, the climber pulls up hand over hand, the tension of the arms keeping the feet from slipping. The stone pilaster on the summit is generally embraced with panting satisfaction, as the height makes the strain upon the muscles considerable. A few moments can well be spared to the view, and few could be insensible to its charms. The distant towers of the Great, New and Nevile's Courts, looming against the dark sky, lit by the flickering lights far below; the gradations of light and shadow, marked by an occasional moving black speck seemingly in another world; the sheer wall descending into darkness at his side, the almost invisible barrier that the battlements from which he started seem to make to his terminating in the Court if his arm slips, all contribute to making this esteemed, deservedly, the finest view-point in the College Alps."

The continuation along the ridge of Hall and up the lantern requires a very sure hand and a very steady nerve, but is straightforward technically.

The Reading Room

The other diversion is a ramble over the roofs of the Reading Room. The way turns aside from the circuit route in the north-western angle of the court. Instead of crossing the balustrade and descending to the Cloister Terrace, we go down a wooden ladder into the Well (H on the plan), through the foot of the Great Library Chimney and down the iron ladder immediately beyond it, on to a flat landing stage. From here a six foot pitch up is made simple by a friendly gaspipe as a foothold and the ridges in the lead above as handholds. The various sections of the roofs on which we now find ourselves have been somewhat whimsically named, from east to west, the Foc'sle, the Bridge, the Quarterdeck, the Cockpit, and the Sterwalk.

From the middle of the Foc'sle a way has been found leading from some iron railings by a staircase window, up a drain pipe on to a small lead roof; thence between a chimney stack and a dormer window up to the crest of the ridge. But as it is almost impossible to go this way without doing some damage to the tiles, the careful climber will do well to pass it by. On the outside of the Bulwark a narrow ledge provides amusing practice in the cat-crawl and is screened from the Officer's quarters.

I Court

"When they were all on an hepe, And behind gonne uplepe, And clamber up on others faste, And up his nose on hyen caste, And trodden faste on others' heides And stampe." --- Chaucer

"Upon the masonry unseen, Secure and swift from 'shore' to 'shore,' With silent footfall travelling o'er." --- Clough

These roofs are little known, and a good deal has yet to be done in the way of thorough exploration. The irregularity of its outline has hitherto prevented the accomplishment of the complete circuit. These climbs were originally undertaken with a view to finding some secluded ascent from ground to roof without the use of the customary window.

Passing into the I Court we have on two sides the high lecture room buildings and behind us the Great Court roofs. The fourth side is blocked by a high wall which defies direct attack.

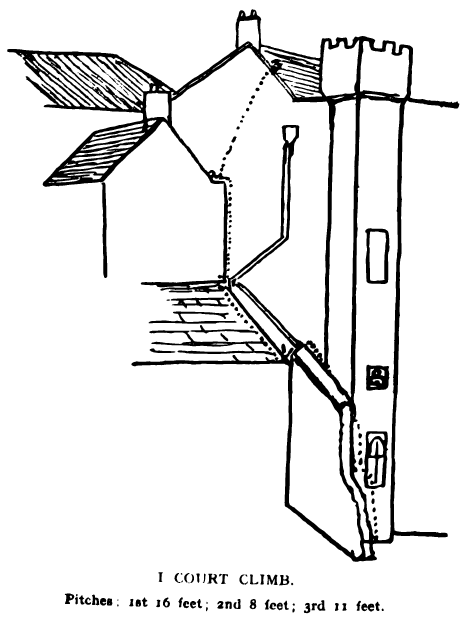

I Court Climb (K)

This starts in the right hand corner as we face this wall.

First Pitch

The "tallest of the party" is used as a staircase; and from his head the leader is able to get a hold for his right hand in the little window of the Turret. By this he can hold himself while his supporter substitutes his hands for his head and thrusts him another two feet up the corner. The visible top of the wall can now be reached; but a sloping coping refuses all hold to the groping left hand, until it tries the exact point where the wall joins the Turret. Here the coping is cut away to allow for a pipe-trap and gives a first-class hold. The right hand joins the left and a kick down against the rough wall yields a much needed relief to the supporter.

Those who prefer to do their climbs on their own hands and feet can "back-and-foot" up "Tank Chimney," at the left hand end of the wall; and walk back to the Turret along it either on the top of the wall of behind it.

Second Pitch

Passing round behind the Turret up a little slate roof, the end wall of a Gable is encountered, which runs parallel to the main building and is joined to it by a broad gutter. The eight foot corner between the two buildings is mounted by the aid of a slanting pipe and the gutter.

Third Pitch

The final roof is now close above us, but the surmounting wall is too high for one man to reach, and the gutter too narrow to allow of two piling up. The method best adopted is for one climber to place his feet as far up as convenient on the opposing galge, and with shoulders leant against the main wall, to bridge the gulf. The second climber steps to his knee, and shoulder, and then pulls up.

This pitch has been climbed direct by leaning far out to the right over space, grasping the basin top of a rain pipe and doing a film-star leap to grasp the square stone coping above. This, however, is unjustifiable unless the roofs are bone dry.

From the roof now reached, an excursion can be made which culminates in a gable commanding an uninterrupted view of Trinity Street. But the roofs traversed on the way are private, and climbers can well afford to renounce its mild pleasure.

Brick Turret (U)

At the corner opposite to the point where the I Court Climb emerges on to the roof stands a brick Turret. This can easily be surmounted by the narrow chimney between the adjacent chimney stack and the Turret walls. From its summit we look down on the parallel-running roof of Great Court, its eaves merging in the ten foot wall which descends from the higher I Court roofs.

Trinity Lane Corner (Q)

To reach the Great Court roofs, the easiest way is to cross the slates from the foot of the Brick Turret (or to traverse along the foot of the chimney stack), and lower oneself carefully on to the coping-edge of the roofs below from the down-slanting end of the ten-foot wall. The spiked railings of Trinity Lane immediately below give the necessary interest. From here it is easy to clamber round a chimney stack and descend by a corner gutter to Mutton-Hole Turret.

Round Chimney Stack

Following the I Court circuit the Great Court roof is kept to until the second side of the I Court square declare itself on our right by the coincidence of its—slightly lower—brick wall. This is surmountable at various points. Perhaps the most interesting route is the balance round the Round Chimney Stack, reached from a Great Court dormer roof. Two uninteresting and large flat roofs succeed; one remarkable for a large glass cupola, and the second separated by a high parapet from the first.

From the end building, the difficulties of an ascent to our present position from the wall above Tank Chimney—difficulties which must be overcome if ever an I Court "complete circuit" is achieved—are more apparent. An excellent view also is obtained of the "Wilderness," the name given to the jungle of steep tiled roofs which fills the space between Great Court, I Court and Trinity Street.

In 1902, subsequent to the first guide, further explorations were carried out with a view to completing the circuit. The climbers failed to do this but discovered that from the end building, a shallow chimney and pipe allow of a descent on to the left-hand gable of a double roof below. The lead gutter on the right makes a handhold for the descent of two steep gable-tiles into the flat bottom between the two roofs. It is a simple matter to reach the top of the second gable; and from here, if from anywhere, the circuit of the Court must be completed, as the wall from Tank Chimney abuts some way below the edge of the steep tiles. Daylight is required to see how far below it runs in, but descent without a rope looks impossible. The return is made by the same route.

Great Court

"To one who has been long in city pent, 'Tis very sweet to look into the fair And open face of heaven" --- Keats

"With tombs and towers and fanes 'twas our delight To wander in the shadow of the night." --- Shelley

"Thou sure and firm-set earth Hear not my steps which way they walk, for fear The very stones prate of my whereabout." --- Macbeth II, 1, 56

The circuit of Great Court, offering as it does, almost every variety of roof climbing difficulty, and hindered, as it is, by every form of authoritative residence, is the greatest feat to be done in the College Alps. The only recorded time is 1 hour 20 minutes; this is probably faster than the average.

It will be convenient to begin a circuit of the Court from the Kitchen Office plateau, as this is easy of access from Nevile's Court and New Court. The way lies up the two steps on to the path behind the balustrade of Hall, and along under that step and fearsome slope until a straight drop above the Master's Lodge puts a stop to further progress, and compels the party reluctantly to climb the roof of Hall. This famous ascent is fully described in the chapter on Nevile's Court. On coming down to the bicycle track at Palisado Corner, a wooden erection (the Palisado in question) is found on the right hand side. This fanciful creation of a former master is passed by gripping the slats behind, at the further low end, and doing a Holywood swing on to the narrow ridge below. A skylight must be carefully clambered over, and then the main ridge of the Master's Lodge looms in front.

Three alternative routes now present themselves. Those whose boldness outruns their discretion may walk along by the battlements on the court side. This means passing in front of nine windows, many of which belong to bedrooms. There is a perfectly practicable though more laborious route on the western face, which means going up and down the gullies formed by several gables. This route is entirely screened from the view of porters, and reduces the number of windows passed to four, but four is sufficient for the route not to be recommended. The only satisfactory plan is to choose a cloudy night when skylines are not clear-cut, and to crawl along the ridge. The only obstacles are two chimney stacks which necessitate somewhat awkward traverses. In the corner behind the Ghost Turret this ridge debouches on to the almost flat plateau which forms the roof of A, B and C staircases.

At the far end of this rises the wall of King Edward's Tower. In order to climb this one man kneels down just to the left of the crest of the ridge, and the leader climbs to his shoulders, getting what help he may from a window on his right. The kneeler then rises to his feet and this enables the leader to grasp the lead bowl at the top of a rain pipe, and using as a foothold a narrow ledge above the window, to pull up on to the battlements and gain the top of the tower. The rest of the party then come up on the rope. Rumour has it that this pitch has been climbed direct, by means of the rain pipe. If by chance the clock should strike when the party is on top of the tower, it is desirable to avoid falling into the court out of surprise, as this may lead to discovery.

A long vista of pinnacles all along the roof of Chapel now comes into view. Each one glimmers whitely above the darkness of the roof, shutting off that secluded Arcadia from the bustle of the court so far below, and from the view of the dignified and complacent porter standing on the steps of the gate. While from the east end of Chapel, at an immense depth glares and roars the traffic of Trinity Street, as far removed into another and a noisier world from the academic activity of Great Court roof. The descent is made by a rope doubled round one of the battlements on to the lead in front of the attic windows of E staircase. And so we come to the Great Gate.

"Until we came unto the city wall And the Great Gate; then none knew whence or why Disquiet on the multitude did fall." --- Shelley

There is always something romantic about the last great peak of a range to fall. For years the Great Gate repulsed all attacks, from the determined assaults of the pioneers onwards, and only in 1927 was it conquered. It is more fortunate than the Matterhorn; fixed ropes and chains do not festoon its sides, and it is not the hallmark of an old roof climber to have a photograph of Great Gate somewhere about his house. Even now probably the parties that have reached its summit could be counted on the fingers of both hands. But it has fallen upon evil days. The drain pipe has been renewed, and it is no longer considered one of the hardest of Trinity climbs. But its day will come again. Old age creeps upon every pipe, and will upon this one in its turn. Then climbers will be forced to use illegal methods --- God forbid the firing of rockets of crossbows, but perhaps the throwing of balls of string from side to side --- in order to make their peak; or else give up the Great Court circuit and sigh for the good days of old.

The method is to grasp the pipe with both hands and to walk up in the shape of a capital D, with the feet as close to the hands as possible. About half way up there is an awkward two feet, where the space behind the pipe is filled with rubbish, and the frantically scrabbling fingers can scarcely find a hold. When the bowl at the top of the pipe is reached, the body must be raised until the chest is level with the hands, and then the left hand reaching quickly out, high and wide, can grasp the embrasure of the battlements. The right hand joins the left, and a pull up brings the feet to he bowl; and the last step is easy.

The corner turrets are interesting and moderately difficult. The descent is made in the same manner as the ascent; or, for those who prefer it, by a rope doubled round one of the battlements.

A long stretch of leads punctuated by ankle-wringing drainholes, most difficult to avoid in the dark, brings one to the corner by Mutton Hole Turret. The passage round the back of this causes no trouble, and if the temptation to wander aside on to the roofs described in the I Court chapter, be resisted, the way lies along another stretch of leads to the wall of Queen Elizabeth's Tower.

If sufficient energy is still available, the rain pipe above a dormer window provides a route by which the Tower can be climbed direct. A less exhausting method is for one member of the party to adopt the rôle of ladder and lie against the slope of the roof. The others ascend by him to the crest of the ridge, from which it is but a step to the battlements. The corner turrets again provide an interesting wayside problem.

The same two routes offer themselves as alternatives for the descent, and yet another stretch of leads brings one to the foot of the kitchen pitch. From the flat roof of a dormer window below the wall, the cornice above can be reached by long arms, and a short jump will bring it within the compass of the shorter brethren. A foot-hold on a ledge well out to the right makes the pitch straight-forward if strenuous. A friendly hand will remove all difficulty. After surmounting the balustrade the climber finds himself back on the Kitchen plateau, and the great feat has been accomplished.

The Chapel

"Now walk the angels on the walls of Heaven." --- Marlowe

"And I 'eard the brick and the balks rummle down As the roof gave way." --- Tennyson

Chapel has suffered severely in recent reconstructions, being especially unfortunate in that the alterations were at a little distance from the peak itself. The moving of the Fellows' Combination Room from the north side of Great Court to its present position has rendered impossible the old climb on King Edward's Tower, by which the roof of the Chapel could be reached direct from the ground. The only way by which the summit of Chapel can now be reached is the long business of accomplishing the greater part of a Great Court circuit.

There is, however, a possible route, not yet exploited, by which Chapel could reassert its old claim to be considered a separate peak. After passing through the arch under King Edward's Tower and turning to the right towards the Vestry, a wooden bridge will be observed directly overhead. If the explorer climbs on to this he will see a deep sunk window in the corner of the tower nearest to the bridge. This can easily be reached; above it come eight feet of exposed climbing, two large drain pipes alone providing holds. This is the crux of the climb. If this pitch can be surmounted and the parapet above gained, it is a simple matter to reach the A B C staircases plateau, at the point where it meets the west wall of King Edward's Tower. That wall can be climbed in the method described in the circuit of Great Court, and the roof of the Chapel gained.

The Library

"Ω μοι γενοιτ αν αιθερος θρονος" --- Aeschylus

"Ne can I tell, ne can I stay to tell This part's great workmanship and wonderous power, That all this other world's work doth excel, And likest is unto that Heavenly tower That Jove hath built for his own blessed bower." --- Spenser

"They dreamt not of a perishable home Who thus could build. Be mine in hour of fear Or grovelling thought, to seek a refuge here." --- Wordsworth

A certain halo of mystery and myth which surrounds the Library makes its ascent the most cherished project of the young roof climber, while its inherent climbing properties win for it from the oldest the first place among Trinity ascents. The variety of ways by which it is traditionally supposed to have been climbed is only equalled by the notability of those, from Byron downwards, to whom ascents are attributed. Hardly a college generation passes without its decorated statues of legend of a pipe ascent "vouched for by the porter." Reduced to hard facts, the majority of these (concerning which anything is discoverable) prove to have been either accomplished on chance-found ladders, or up the Turret stairs, breaking I at the window below and out at the door above.

Anyone who surveys the Library calmly and critically must come to the conclusion the Sir Christopher designed it primarily for climbing and only incidentally as a book store. It is too perfect to be an accident. Consider each detail. That little halfway ledge, undercut, so pedants and architects say, for rain drip, but actually set as a handhold to solve the southwall traverse. Those wall decorations, so spaced that the Ornamentation Climb approaches so very close to, but does not cross, the narrow line that divides severity from impossibility.

"The blinding walls Were full of chinks and holes" ---

Tennyson remarked, with his usual accurate observation; and then, seemingly, returned to his rooms in New Court, blinded to the revelation that here, for once, the Genius of Architecture and the Poetry of Wall Climbing had been realized in a single dazzling mural vision. Let us return to earth and consider all the climbs in turn.

Starting from the ground, there are three routes by which we can reach the continuous ledge which encircles the Library at half its height. The section of this ledge which faces Nevile's Court is called the Cloister Terrace and can be reached by Castor and Pollux. That facing out over the Backs is called the River Terrace and can be reached by the Gateway Column Climb.

Castor and Pollux

These are two similar but converse chimneys, starting from the corners of the grass in Nevile's Court. After ten feet of constricted climbing, ledges on either hand enable us to reach the capital of the great column. A toe carefully placed on the stone bar half-way up the window assists towards the movement up over the cornice and on to the Cloister Terrace.

The Gateway Column

This is perhaps the prettiest climb in Trinity [3]. It is on the River Face of the Library and starts up the bars of the first window to the left of the Central Gateway. A "mantel-piece" movement, assisted in the case of a long reach by a "picture rail" high above the right hand, lands us standing on the ledge above the window. The square capital of the Gateway column now comes about chin high on our right. Surmounting this we find ourselves in a horribly uncomfortable position crouching under the projecting cornice. Using undercut holds in the stone, we stand up and lean boldly outwards, reaching a long arm out and over the edge above until the hand finds— mirabile dictu—a firm iron ring. When this has been grasped it is comparatively simple to roll up on to the River Terrace. For the ring-of-grace thanks are due to Trinity Balls of the early twenties. For this climb the party should be roped, and the ring makes an excellent belay. To descend by this route needs very delicate balance, and the climber should bear in mind that a prowling porter under the Library may obtain a closeup view through the window bars of his descending legs.

Circuit of the Library

In addition to the three routes described above, the encircling Terraces can be reached from New Court and Nevile's Court. We will assume the party to be approaching modestly from New Court, and to have climbed out of the Dip and down into the Hole. The last step into the Hole is awkward, the bottom being about six inches lower than anyone would have thought possible. After surmounting a simple short pitch, we stand on the bicycle track leaning over the balustrade in the south western corner of Nevile's Court. The Eastern face of the Library must now be traversed.

The Cloister Terrace

This falls into three clear divisions.

Terrace Groove One

From outside the balustrade some five feet of descending chimney work, between the wall and a column on the Library, bring our feet on to the square base of the column; and thence a threefoot step lands us on the terrace, close to the top of Castor.

The Cloister Terrace

This is a delectable spot for the contemplative climber. Here, as long as he is not wearing a white sweater and does not sneeze, he can sit in the shadow at the base of one of the great pillars, and gaze with Olympian serenity upon peripatetic porter, passionate poet of professorial philosopher as they pass below him upon their lawful occasions.

Terrace Groove Two

At the further end of the Terrace, at the top of Pollux, an upward chimney climb, identical in character with that of Groove one, brings us up over the balustrade and so again to the bicycle track. A wooden ladder leads down into the well (W on plan), which is the crater under the Library Wall corresponding to the Hole at the other end of the face.

At the bottom of the Well, the full truth of the Great Library Chimney is first revealed to us; the frail stack soars fearsomely into the darkness far above our heads. But its ascent is not our present object. We cross the bottom of the Well into the very bottom of the Chimney and pause shuddering on the brink of an equally fearsome precipice above the empty darkness of the Master's Garden.

The Long Step

Descending three rungs down an iron ladder that leads down from the foot of the Great Chimney, we reach out a foot to a leaded jutting corner, and using as a handhold a brick ledge, which continues round the corner, sidle round on to a smooth lead slab on the northern face of the Library.

"One step enough for me"

But for those who

"Linger shivering on the brink And fear to launch away"

there is an easier, though longer, bypass, climbing down the ladder, up on to the Stern-walk and up the lead slab mentioned above.

Staircase Peak

The small subsidiary peak formed by the roof of the Library Staircase now rises on our right. It is ill worth ascending for the sake of the view. The river is directly below and seems to issue from an arch under our feet; and from it lighted windows in St. John's are reflected up without a ripple. Their Chapel Tower shines magically in a silvery upcast of light above the black shadow of the interrupting Courts. Even St. John's New Court across the river contrives to take unto itself wonderful alternations of soft light and darkness. A broad ten-foot ledge completes the passage of the Northern Face. We are assisted on to this by a lead rib of the Staircase Peak, which is polished as smooth as St. Peter's toe by the hands of generations of climbers. This ledge turns the corner and becomes ---

The River Terrace

This peaceful walk is as broad as the Cloister Terrace and doubles its width above the three gateways. Taking care not to stumble over the frequent iron rings, we make our way along, past the top of the Gateway Column, and so come to the Wet Bobs Traverse.

The Wet Bobs Traverse

The name has authority; the position of the hands in traversing being that which they assume, close to the chest, at the end of the stroke. For the feet we have a ledge about two inches wide and for the hands an undercut hold at a very comfortable height. But the strain on the arms and the exposed position make it unwise to dawdle unduly on the traverse.

This brings us back to the Dip, which we leave by one or other of the methods described in he New Court Chapter. And so complete our circuit.

There are two routes from the half way terrace up on to the roof of the Library.

The Ornamentation Climb

--- is at the southern end of the Nevile's Court face of the Library. Purists start from the bottom of the Hole and there are two alternative routes; a, to use a press-off the Library, a stucco corner and a lead pipe to help us on to the battlement-edge of the wall parting the Hole from the Dip. b, to gain the balustrade above Nevile's Court; this is thought to be the harder route. In either case we step up and across on to the sill of a blind window right (or left in case of a) of the central arch. Here a long reach can use a little ledge above for balance, a short one must press against the window top. Using the stone ornaments for handholds, we step across on to the capital of the arch pillar; and thence walk up the arc of the string course above the arch, holing on to as many petrified vegetables as may be. To balance up on to the central boss of the arch we can use a press hold on an undercut moulding under the cornice. Standing on the boss we have already an elbow over the cornice, but it is reassuring to take a steadying finger hold in a loose lead seam (this should be no more than a caress for the sake of future climbers).

The climb is less severe than it looks. But it is highly and deeply exposed, and a rope is to be recommended. The descent, with the movements in reverse order, makes a very pretty climb. The last man can use a doubled rope passed through the balustrade above. (The stone is rough and sticksome verb sap.).

The Great Library Chimney

--- is the second route up, though it stands first in historic order and may now be termed a classic climb. It is formed by the lofty chimney stack facing the Library on the Nevile's Court Wall above the Master's Garden. The height from the well to the top of the Library balustrade is 31 feet. Nine feet from the bottom a narrow ledge runs round the stack; 9 feet higher the chimney sets back, leaving a broad sloping ledge. Nine feet higher again projects the Library Cornice, seeming almost to close the opening between stack and wall.

The climb can be done in various ways:

a) Puristically, it may be chimney-swept throughout. Though very exhausting, it is straight-forward once the principle of back-and-foot climbing has been mastered. Some climbers prefer to have their backs to the chimney so that the hands can use its rough brick edge; others feel satisfaction from having the whole Library behind them and from being able to see that their feet do not stray from the straight an narrow way of the chimney.

b) More elegant, is to traverse out from the roof gable; and thence "bridge" the chimney, using a small foot hold in the Library wall fro the movement. c, An interesting and difficult variation, is to climb the chimney for about 16 feet, move across and stand on the sill of the blind window in the Library wall, and thence climb the face by the Ornamentations, as is done in the "Ornamentation Climb" at the other end of this face of the Library.

We have now scaled the Library at both ends of its noble chain, by routes worthy of its Olympian tableland, floating cloud high above time and night watchmen. The seal is set by saluting the three Muses and Geography lightly upon the cheek, or more hardily upon the lips. The globe of Geography is loose; and the figure most southerly but one, Clio or Hope according to your school of thought, must now be approached cautiously, for the volume at her feet shows an inclination to join its fellows below. Then care-and rope-free, we may wander hither and thither; with the collective wisdom of the ages safely locked up and trodden under our feet, with the rival aspices of Cambridge creeds and cults opening out in vistas of unreal transparency about us and illuminated only from below, and know our own heads and dreams to be set high above them among the stars. Thereafter how often and how often shall we not remember it in after lower life.

"Morn in the white wake of the morning star Came furrowing all the orient into gold. We rose, and each by other dressed with care Descended to the court, that lay three parts In shadow, but the Muses heads were touched Above the darkness from their native east." --- Tennyson, from The Princess

Wayside Problems

"All places that the eye of Heaven visits Are to the wise man ports and happy heavens." --- Richard II, 1, iii, 275

"Ich bin herunter gekommen Und weiss doch selber nicht wie." --- Goethe

Innumerable small problems offer themselves in every corner of the college. Only a few need be mentioned.

Nevile's Court

The Library Pillar

This must stand first, for it is one of the freshman's places of worship, and few have passed it by since it was first discovered after a feast in Hall in 1895. It is the corner column of the Cloister arches at the New Court end of the Library. The circuit of the column has to be made on the ledge about eight inches above the ground. A nice balance is required, as the stone is becoming so smooth that it affords only a very slight friction grip. A distinguished literary don once performed the feat six times in a minute, but many hours may be spent on it in vain. The circuit can also be made with the use of only one hand.

Close by, at the end of the line of columns under the middle of the Library, stand two about three feet apart. An exacting feat is to back-and-foot up between these, hand traverse round the capitals of both, and back-and-foot down again.

Less strenuous circuits may be made of the smaller pillars of the court, hands in pockets.

The classical fantasia with which Wren has adorned and harmonized this side of Hall may be climbed between the side pilasters. As the ascent is one of "art for arts' sake," the descent must be made by the same route.

The cornices round the court and the first floor windows can be reached by way of the pillars in several places. Whether the continuation of the traverse be legato or staccato must depend upon the room-tenants.

New Court

Very little has been let fall here. The low roof on the kitchen side of the entrance to Nevile's Court can be reached by a pipe whenever the herbaceous border and creeper do not run too wild. From this roof a firm pipe, well clear of the wall, runs right up to the roof, but it is unseasonably swept by avalanches of plaster.

The New Guest Room Traverse

The square of lead roofing between, and rather below the southeastern corner of the Nevile's Court roof, and the Kitchens plateau, harbours the kitchen ventilator, and is the starting point of a short and sensational climb. Proceeding to the corner of this roofing which is nearest to the kitchen and looks across upon Bishop's Hostel, a narrow brick string course running across the kitchen wall will be observed. The feet once upon it a stretch is made to the right, and the right hand at its full extent can grasp a small projecting lead pipe. The left hand relinquishes the parapet of the lead roofing and the hands are changed on the minute horizontal pipe. A vertical rain pipe can now just be reached with the disengaged right hand and we shuffle along our string course, squeezing behind a pair of telephone wires which descend we know not whence to arrive we know not where. Once on the far side of the pipe another long stretch of the right hand brings the vertical edge of a window moulding within finger-reach, and a somewhat relieved climber can sit upon the window ledge and take breath. From this point the climber must either make an entry into the room, or return the way he came. A first attempt at this amusing climb may be safeguarded by a rope from the Kitchen roof above.

The Hostel

A fine brick chimney (O) lies between the wing of the Hostel nearest to New Court, and the main block along the Lane. It has for its exit, if desired, the staircase window of E staircase. The low kitchen roofs can be attained on the Hostel side by a double pipe in the recess behind the Lane Tower of New Court; and from thence various first floor windows. But further exploration of the Kitchen Range is eminently desirable.

Great Court

On the Hall side of Queen Elizabeth's Tower between the turret and the wall, and again in the corner by Muttonhole Turret, a way has been found to the first floor windows. These possibly might be continued to the roof. Sociable traverses between a number of the first floor windows are recorded.

The Chapel Porch is a tempting though porter swept goal (1900). It is so still (1930).

The Hall Porch is a famous test of style. It can be climbed by either pillar with the help of the disused lamp-hooks. 'The Master's Leap' (Dr. Whewell cleared the whole flight of steps to the Hall in cap and gown) has not been repeated recently by his successors.

The Fountain

Tradition has now begun to assert that this was first climbed by the omnivolant Byron. Of recorded ascents there have been few. Technically, it is one of the stiffest, and to the eye of authority one of the most exposed ascents in College. The waterpipe inside holds the clue.

The area behind Chapel has not been thoroughly investigated since its remodelling. From the Vestry roof a certain height is attainable up chimneys formed by the buttresses. Various syncopated scrambles suggest themselves, notably during organ recitals. An inviting chimney offers to the right of an eminent ethnologist's front door.

Whewell's Court

The nature of these roofs prevent any routes being made up them with safety. There is an attractive couloir on the grass plot side of the Sidney Street gate. The unclad 'statu pupillari' in the centre is said to commemorate the pose of the first freshman who fell out of it. The chimneys between the projecting windows in the Billiard Table Court will go to a certain height. There is also a promising double drain pipe in 'the breathing space' between the two courts.

The Bridge, on the Backs

This is a very attractive problem, involving a heavy penalty for failure. The object is a descent on to the base of the pier, starting with the feet on the semi-circle of the arch and using the ledge below the parapet and the crested shield for successive handholds. The Southern, Clare face, is the clearer of vegetation.

The circuit of all three Courts in one night has only once been made; it was done during the First and Third Ball of 1929 in 1 hour 56 minutes. This is hardly a Wayside Problem, but there is no other place in which to mention it.

The adventurous reader has now been conducted up, down or along all the roofs best worth visiting in our district; and the termination of the expedition gives him the desired opportunity of retiring and washing off the sooty illusions. The Guide begs permission to do likewise. An expert will, doubtless, find many faults in it, both of commission and omission, to criticize and improve upon, but its existence will have been justified if it has succeeded in providing the young stegophilist, making his first night venture upon the Trinity Roofs, with a clue, however poor, to the creditable unravelling of their somewhat complex mazes.

"Inde pedem sospes multa cum laude reflexit, Errabunda regens tenui vestigial filo; Ne labyrintheis e flexibus egredientem Tecte frastraretur inobservabilis error." --- Catallus

And so to bed.

Footnotes

| [1] | Published Eton, 1905, Spottiswood and Co. Ltd. |

| [2] | The "bicycle track", which is frequently mentioned in this volume, is the broad lead track behind the balustrade on the two longer sides of Nevile's Court. |

| [3] | This climb might possibly be used as an illicit way into College, but because of its severity it is recommended for such a purpose only to those whose permanent residence inspires them to a thorough knowledge of the byways of their College. |